Posted on June 19, 2017

It might sound strange at first to hear of a professor in human oral pathology who researches animals, but Prof Erich Raubenheimer* has spent over a quarter of a century studying the great African Elephant (Loxodonta africana). What started as a challenge by an American researcher to bring something unique to the international research community, soon became so much more than science and one of his greatest passions today. Raubenheimer is an oral pathologist by trade and developed expertise in the diagnosis of metabolic diseases affecting the human skeleton. Unlike most laboratories that demineralise bone in order to identify pathological changes, Raubenheimer exploited the examination of bone in its mineralised state in establishing a comprehensive diagnosis. Although his main research interest is the study of metabolic diseases of the human skeleton, in an unexpected turn of events, his expertise in the analyses of mineralised tissue were applied to the study of elephant ivory.

Initially he focused on studying the chemical composition of ivory and providing a biological explanation for the unique appearance thereof, which contributed to ivory becoming the desired material for the creation of works of art. Through a growing awareness of the rapidly declining elephant numbers resulting from ivory harvesting, his interests soon shifted to the impact of human-elephant interaction on their incredibly developed social structures.

Never letting the lack of funding inhibit his research, Raubenheimer started a small safari company taking tourists from abroad into free-roaming elephant territory to fund his research. It was on these trips to Angola, Zambia, Botswana and Namibia that Raubenheimer was able to experience the majesty of the free-roaming elephant of Africa. On each safari he became more aware of their social hierarchy, discipline, empathy and intellect which eclipse those of human societies in many respects.

Elephants display characteristics of a close-knit family, with a formidable dominant female controlling the fate of those under her leadership. The matriarch, with her characteristically large tusks, acquires her position through her power, wisdom and personality – she is an extrovert and her decisions determine the fate of the entire family unit. She has an intricate knowledge of resource availability throughout the climate cycle and determines the migration patterns for optimal provision of food and water to those she is responsible for. The longest migration path is that of the small clan desert elephant in Mali (the northernmost elephant on our continent), who migrate 1 700 km annually on a path that passes through a significant portion of the Sahara Desert. The matriarch knows the physical abilities of each member of the herd – and the herd follows her with full trust on this great trek.

Migration paths play an important role in the genetic diversity of trees and plants as well. Elephants are great seed dispersers and the spread thereof in their dung maintains the genetic diversity of plants on the African savannah and beyond. Raubenheimer noted that through the spread of seeds stable elephant populations around the Sahara Desert could retard and even reverse the enlargement of this barren region.

The matriarch also plays a fundamental role in the reproduction of the herd. By exerting her dominance over weaker animals and tuskless females in the herd, she manages to suppress ovulation in these cows, maintaining the genetic quality of the family. Raubenheimer explains that in a natural environment free of human interference, congenital absence of a tusk, which follows on a gender-linked spontaneous mutation, affects 4.62% of new-born female calves. The emotional dominance of the matriarch, Raubenheimer maintains, suppresses the production of pituitary hormones that control the oestrous cycle in animals low in the hierarchy. In this way, the matriarch preserves the ivory-bearing genome by allowing only selected members of her family to bear offspring.

Among some of their important uses, a tusked elephant can effectively fend for the family's safety, remove bark and branches from trees and dig for water and salt. Elephant, like humans, are either right or left tusked. The shorter tusk generally indicates the tusk used most frequently and indicates the side to which a particular animal is oriented.

Sadly, it is the very ivory matriarchs preserve through selection that has become the reason one elephant is shot every 15 minutes on our continent. Hunting and poaching with modern rifles over many decades have led to a disappearance of the legendary big tuskers from the face of our continent. Hunters and poachers alike shoot the biggest tusker they can find for trivial motives like the trophy value of the hunt or the monetary value of the tusk. The animal selected is frequently the matriarch, as with her large tusks and leadership attributes she is usually the member of the family that confronts the aggressor head-on. With the death of the matriarch, years of experience, leadership attributes and knowledge of the environment is abruptly terminated and the family unit is plunged into disarray until new leadership is established. During this period, the smaller animals in the leaderless family fall prey to large carnivores and the arrest of migration may even be detrimental to the survival of the remainder due to resource over-utilisation. Raubenheimer has been witness to this sad phenomenon. Poaching is driven by the high price ivory fetches in the markets of the East, which, due to demand, soared to more than 3000 US$ for a 35 kg tusk. Poaching of elephants is a thriving industry, the profits of which frequently finance civil wars in central Africa.

Raubenheimer has proven through his research that the percentage of tusklessness increases in areas where ivory harvesting is rampant. While it is strange to picture a herd of tuskless elephants, disappearance of the ivory gene may be nature's answer to the elephant's plea for survival.

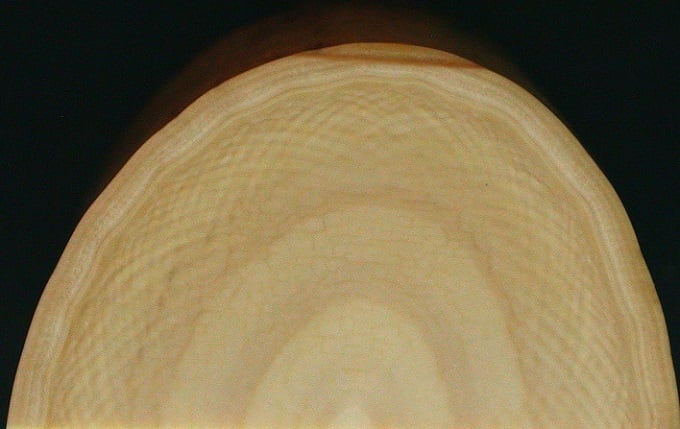

A cross section through a tusk demonstrating the unique chequered pattern created by the two semi circular alternating light and dark bands radiating from the centre of the polished surface

Elephant ivory is the equivalent of human dentine and is unique in that it demonstrates a harmonious diamond or checked pattern on polished surfaces. Microscopic examination shows 40 000 to 60 000 perforations per square millimetre that pass through the full thickness of ivory. This makes ivory one of the most microporous materials known to mankind. The serpentine course followed by these perforations reflect light differently, which explains the radiating and alternating light and dark bands, creating the pattern which can be seen with the naked eye. The trace elemental concentration and distribution in ivory also provides great insight into the nature of the diet of an elephant. The composition of the vegetation is a reflection of the minerals in the soil. Analysing the trace elements in ivory which are taken up in the vegetation consumed and incorporated in ivory, makes it possible to speculate on the geographic location of the elephant from which the ivory was sourced. The forensic potential of this finding is enormous as science can now contribute to the determination of the location of illegal ivory harvesting.

One cannot help but feel inspired after time spent with Raubenheimer. His life's path shows the fullness that research can bring – with his work taking him across the African continent. The study of one field of science can lead to something completely different, creating a new great passion and leading to major contributions to the pools of knowledge.

*For over 30 years, Raubenheimer was Professor and Head of the Department of Oral Pathology in the School of Dentistry at Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (previously known as Medunsa). He now serves as an Extraordinary Professor in the Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Pretoria. He is also a Senior Consultant at Ampath Histopathology Laboratory in Pretoria. His love for elephants continues to inspire his research and trips across the continent.

Copyright © University of Pretoria 2024. All rights reserved.

Get Social With Us

Download the UP Mobile App